If a collection of short stories can be like a road trip, that’s what Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart is. GennaRose Nethercott’s characters are constantly in motion: traipsing up and down the Eternal Staircase; traveling to stay with a friend in Switzerland whose barn guest room holds a strange secret; even just moving from room to room in a house. Or becoming a house. Florists go in search of flowers that are also, or actually, animals. A girl who is always drowning goes outside to smoke.

The restlessness is rich, palpable, and deeply appropriate alongside the kind of magic Nethercott conjures up. You could say she’s working with folktales, but how many of these do you recognize? It feels more appropriate to say that she takes the language of folktales and fairy tales—the way people are often named for what they are; the way magical things simply happen, no explanation necessary or even permitted—and mashes it into a sort of dusty-road Americana that lingers in the back of the throat. Roadside attractions, rambling sons, heartbroken artists: Nethercott is writing with old world style, but creating her own new world order.

Her debut novel, Thistlefoot, had this same restlessness, dancing through different paces as its central characters traveled the country in their chicken-legged house. It borrowed from established tales (not least the story of Baba Yaga) but wove in women in leather jackets and siblings who put on puppet shows. History, but also statues that get up and walk.

If you love the richly magical work of Kelly Link, the uncategorizable tales of Helen Oyeyemi, stories by Aimee Bender, Neil Gaiman, Karen Russell—you will likely find much to enjoy here. All the more so if you are the kind of person who sometimes just wants to pick up and leave your life behind, or hopes that under the next leaf you turn over there may be some creature you have never seen before. Nethercott’s stories start with the Eternal Staircase, a tourist attraction that claims the attention of the unwary; she writes in warning signs and directives to visitors right alongside the tale of two teens and their messy summer.

Later, the title story is a bestiary, but woven through the entries of creatures that never were is the story of three florists with flowery names, their fraught relationships to each other and the creatures/flowers they write about. “Drowning Lessons” is teenage loneliness in a life jacket. Poor Sophie just drowns in everything (she has to drink her whiskey out of a sippy cup, lest it reach for her throat), and her poor brother watches her suffer, takes her to a party, gets rejected. There is almost nowhere for her to go.

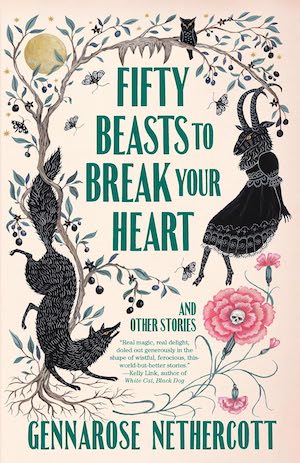

Buy the Book

Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart

There are monsters here, sure, depending on your definition of monsters—which is kind of the point. Nethercott writes briskly but vividly, lingering over her creations but sometimes slipping by the horrors so quickly that they take a moment to register. (They always do catch up.) And sometimes the horrors are beautiful, inevitable, metaphorical in a way that makes perfect sense; you’re nodding along, thinking, yes, of course, a woman whose career is being smothered by her too-perfect partner would become a house, the thing he lives in, the thing that holds him up and keep him safe. Of course she would. Of course a town would turn a woman into death herself so she could go into the woods to fetch dinner.

In “Thread Boy,” an adventuring young man becomes weighed down by all his ties—lovers, friends, connections—but can’t possibly let them go. The characters of the incredible “Possessions” find a spellbook at Goodwill, which seems as likely a place as any to turn up something magical and spiral-bound. There’s a playfulness to Nethercott’s style, and especially in her wide use of forms: a venomous letter, a slippery transcribed memoir, a transformative bestiary, a calendar, a dictionary. The dictionary comes in “A Diviner’s Abecedarian,” a story about powerful sixth-grade girls with a masterful understanding of divination. (Anything to get through middle school, right?)

“A Lily Is a Lily” is a sweet little love story right up until it’s not—until it becomes a cautionary tale about the kind of young men who only want the idea, not the reality, of a woman. (The last lines of Nethercott’s acknowledgement have both bite and a smiley face: “Last, let’s give it up for my exes. If you think it’s about you, it probably is.”)

The title, after all, includes the words “to break your heart,” and there are a lot of hearts broken in the course of this collection. It isn’t heavy, necessarily, but it is true, full of heart and weight and feeling just as it’s full of cleverness and vivid imagery. “Drowning Lessons” is a story about teens at a party, but it is also about class rage, about want and need and yearning, and the ways in which our hearts and our bodies might lie to us about what we need:

“The desire mounts and mounts until eventually, the desire is so irresistible that you willingly allow water down your airway and into your lungs. You choose this. Every cell in your body insists, This. This is what you need. There is wanting and there is yearning—and then, there is a lung filling with water.”

Fifty Beast to Break Your Heart stars with a list of rules that are about a roadside attraction, but might well be for an unwary entrant to fairyland. (“Do not enter the Eternal Staircase after 8 p.m.”) It ends with forbidden plums. The pages and tales between are restless, playful, wise, heartbroken and rich. If you yourself are already restless, this book may make you more so. But perhaps, when you’re done, it might send you off in a new direction entirely.

Fifty Beasts to Break Your Heart is published by Vintage.

Read an excerpt.